Towards transfer learning in molecular foundation models

Are multi-modal molecular foundation models learning transferable representations across biology and chemistry?

tl;dr: Unlocking broad generalization to data-scarce modalities in molecular foundation models may require unified representation learning.

I think we’re on the cusp of a very exciting moment for molecular modelling. We are developing unified, broadly applicable foundation models that move beyond a single data modality. This is exemplified by two moonshot projects.

In biology, new models are integrating multiple interrelated data sources, with the ultimate goal of creating what some are calling an AI-driven Virtual Cell.

In chemistry, Universal Interatomic Potentials aim to perform molecular simulations as accurate as quantum mechanics at a fraction of the cost.

Here’s what I believe is one of the most interesting open and unanswered question right now in developing these ‘omni-modal’ architectures:

Molecular foundation models currently do not demonstrate the same transfer learning capabilities across related data modalities as LLMs.

Can we learn transferable representations that unlock generalization to novel and data-scarce modalities in molecular foundation models?

In other words, what’s our equivalent of how LLMs trained on maths seem to get better at coding?

Missing transfer learning capabilities

Case 1: Structure prediction

Structure prediction entails predicting atomic coordinates of biological molecules based on their sequences. In principle, models output a set of atoms in 3D space, regardless whether the inputs are proteins, RNAs, DNAs, small molecules or another type of ligand. Thus, we would expect models to learn transferable knowledge across all these different modalities.

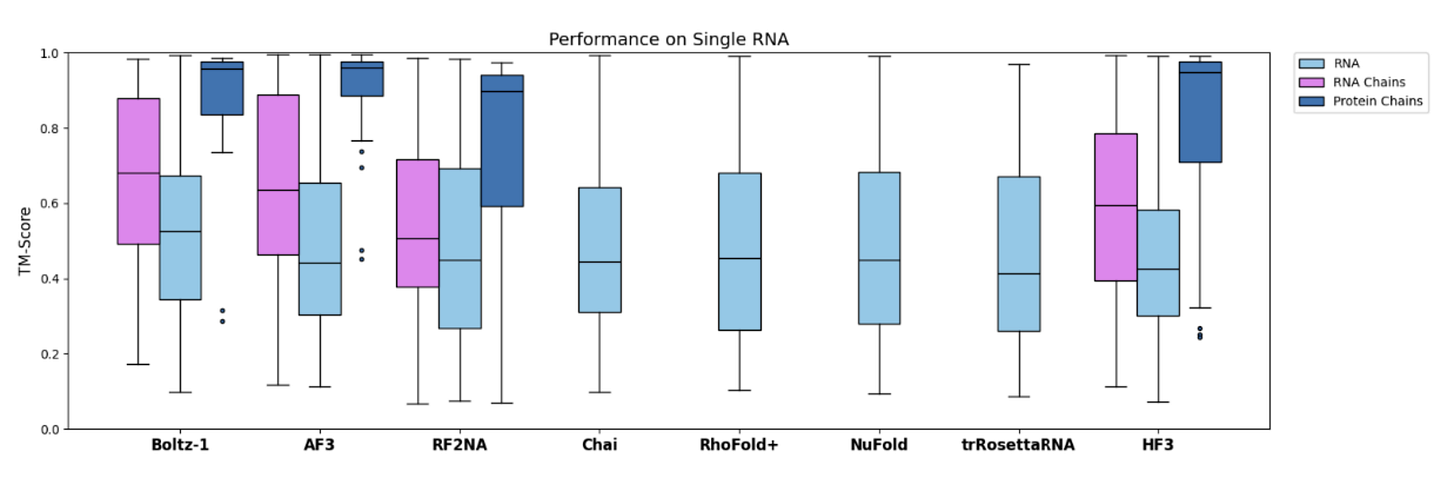

However, I think we have not seen convincing evidence of transfer learning from data-rich to data-scarce modalities. For instance, take RNA monomers. There doesn’t seem sufficient evidence that training on proteins improves performance on RNA-related task. Indeed, at the latest CASP 16, the best automated predictors for RNA were RNA-only models instead of AlphaFold 3.

Similarly, bluesky posts by Martin Pacesa (an expert in designing protein interactions) often hint that protein-only AlphaFold performs at least as well as AlphaFold 3 when given the same sampling budget.

Unfortunately, the AlphaFold 3 paper did not show any ablation studies on transfer learning capabilities. Nor did any of the subsequent reproductions, such as Chai or Boltz. I think that simple experiments where different data modalities are held out to measure performance on the remaining tasks would have been extremely insightful. And I would be really surprised if the teams did not do them internally.1

So truly demonstrating transfer learning capabilities in structure prediction is an open question (which we’ll come back to in a moment).

Case 2: Biological language models

Let’s turn to biological language models, where the answer to the transfer learning capabilities question again seems to mostly be No, for the moment.

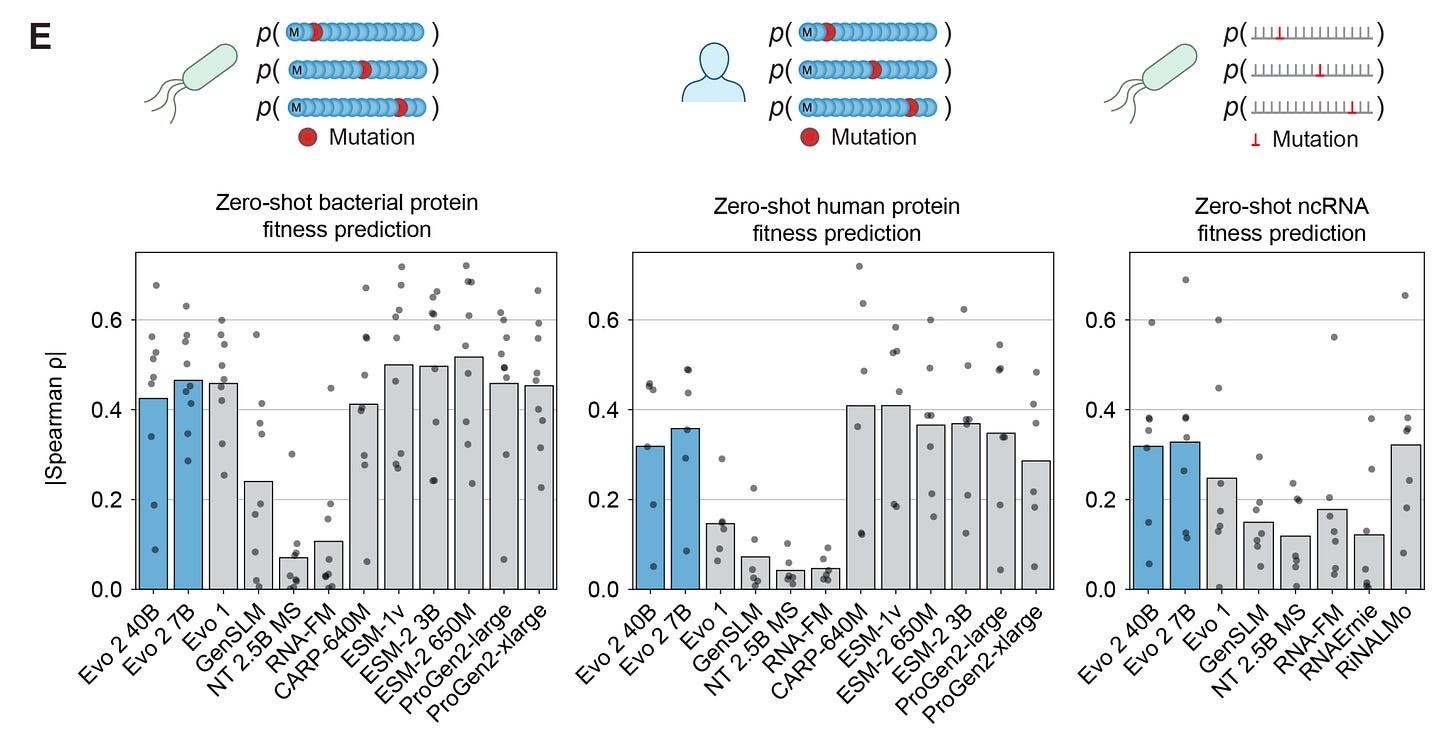

The most prominent omni-modal sequence models are Arc Institute’s Evo 1 and Evo 2. Evo converts all biological sequences to DNA and can, in principle, be used for prediction and design tasks across DNA, RNA, and proteins.

In practice, at least for benchmarks such as fitness and function prediction, there is always an older generation uni-modal language model that matches or outperforms Evo. This is despite Evo using an order of magnitude more parameters (7-40 Billion vs. 650 Million-ish for strong baselines).

Obviously, there is probably a limit to how much emphasis we should place on fitness/function prediction benchmarks for a project like Evo. I think that there’s probably more emphasis on Evo’s generative capabilities, which can only truly be validated via wet-lab experiments (undoubtably under way).

But on the related note of scaling and transfer learning in biological language models:

Pascal Notin and Jude Wells have written informative posts about the limits of scaling in protein language models for both predictive and generative tasks.

Anshul Kundaje regularly shares very interesting benchmarks and rigorous assessment of the latest grandiose claims in genomic foundation models. This latest one was thought-provoking: asking whether being able to predict something well actually advances biological understanding?

Lastly, this sentence from a recent post by Abhishaike Mahajan (Owl Postings) captures my feelings as well:

In general, it seems like many biology foundation models [he’s discussing pLMs and scRNA LMs] made back in 2021-2022 are still decently competitive with models made today, which is a worrying place for the field to be in.

So is there anywhere in molecular modelling where we do see transfer learning capabilities?

Case 3: ML Interatomic Potentials

So called ‘universal’ ML Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are one such success story of transfer learning across very diverse data modalities.

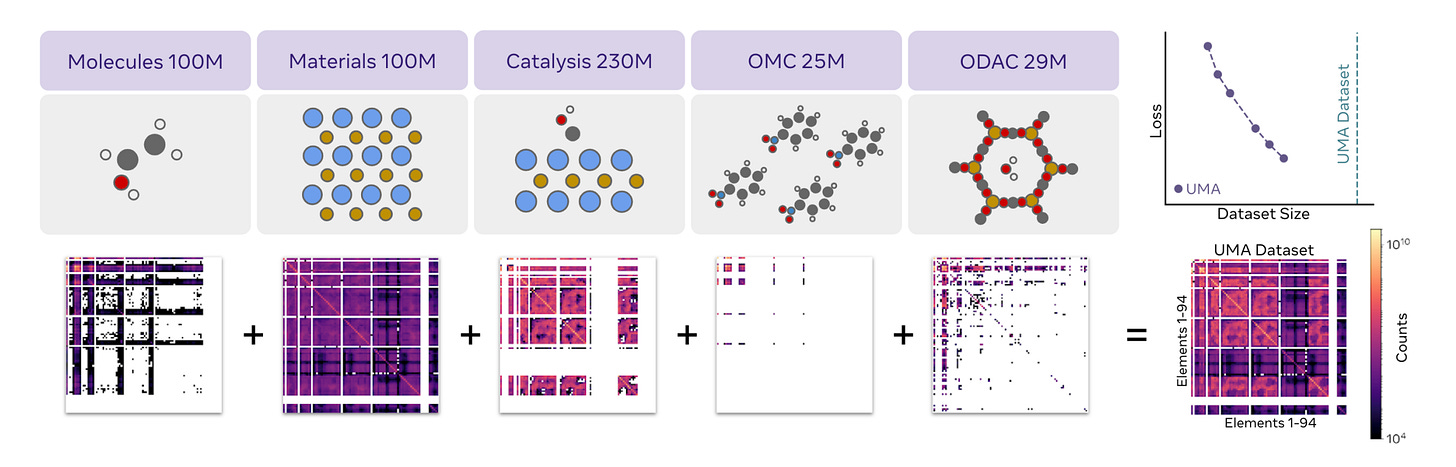

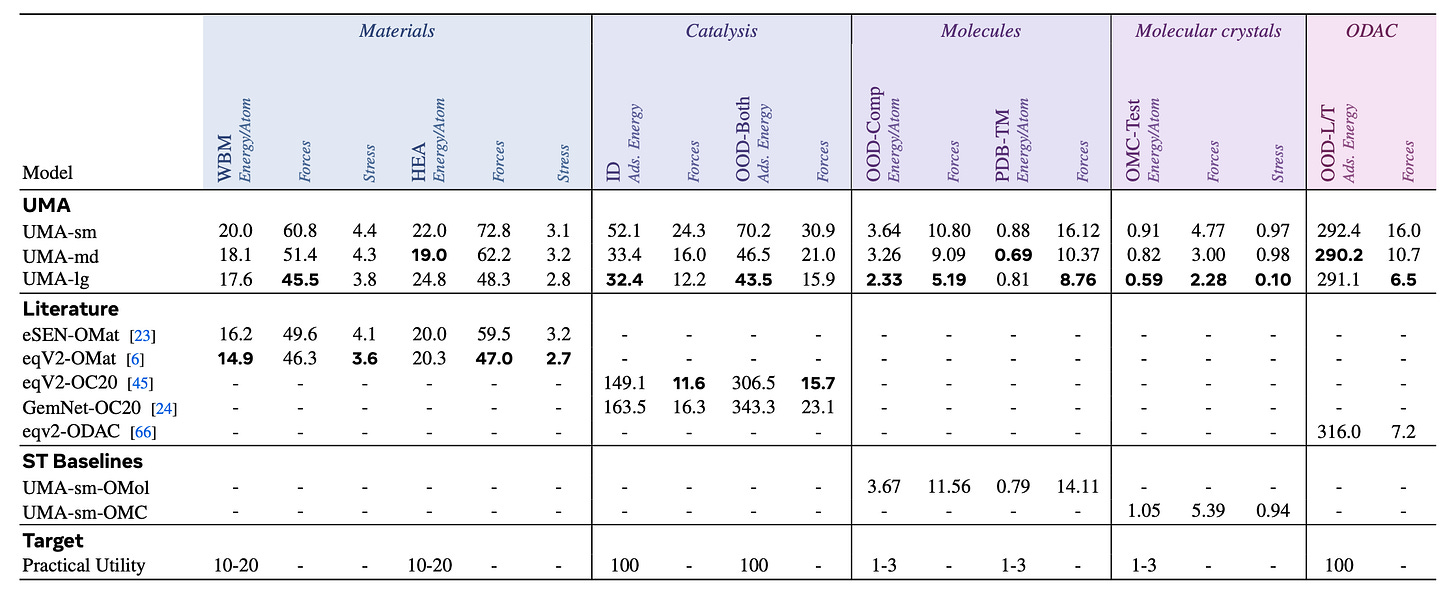

In the latest Universal Model of Atoms (UMA) paper from Meta’s Chemistry team, they jointly trained an Equivariant GNN on inorganic materials, organic molecules, as well as hybrid systems like catalysis slabs, metal-organic frameworks. They also ablated how training the same models on each data source individually performs.

Impressively, the jointly trained UMA benefits from transfer learning and outperforms uni-modal baselines as well as all previous published work.2

I think this result is really exciting! It shows that it is possible to learn general-purpose, broadly applicable molecular representations that benefit from transfer learning across very different types of molecular systems.

What could be the reason for transfer learning in MLIPs?

What intuitions can we gain here?

The importance of unified representations

You may have seen LLM people talk about ‘tokens’ and their informativeness, usefulness, etc.

Transfer learning in LLMs is fundamentally driven by a unified input representation format across very diverse sources of training data. Maths, code, textbooks, chat conversations, and everything in between is all encoded as a set of tokens. Each token is a sub-words or characters - sort of like atomic building blocks of language. As a result of shared tokens, models learn intermediate representations that inherently share information across tasks by design.

On the other hand, the granularity of representations in molecular structure prediction models is at the per-residue level: while the AlphaFold 3 architecture is technically an all-atom model, a large majority of the model parameters are actually dedicated to processing the protein/nucleic acid sequence and multiple sequence alignment inputs (the Pairformer module). The all-atom Diffusion module, applied after the Pairformer has processed the input sequence information, is relatively lightweight. If the different data modalities are represented as separate tokens for a majority of the computation performed by the model, it seems less likely to lead to knowledge transfer.3

Biological language models, by definition, use residues or nucleotides as tokens. What sets Evo apart is that different types of biological sequences are all represented as DNA. However, this may not necessarily be the ideal representation format for transfer learning. To begin with, three nucleotides code for one amino acid, so the model has to learn the triplet genetic code and its highly evolved redundancies from scratch.

What molecular representation has demonstrated transfer learning? The all-atom representation in universal MLIPs. Each atom has its own representation, which the model updates and makes predictions using. Intuitively, this promotes transfer learning because molecular systems across organic and inorganic domains are all processed as sets of atoms in 3D space.

Another key idea in MLIPs that enables generalisation from data-rich to data-scarce domains is the inductive bias of locality via GNNs. The predictions for each atom are based on atomic interactions within a predefined cut-off radius. This means that the per-atom representations capture a strictly local environment around each atom. While organic and inorganic molecular systems are globally very different, there may be shared local patterns that are transferable across domains.

This is in contrast with the Transformer architecture used for structure prediction and language models. Transformers are more expressive and not constraint to be local, as we discussed in my last post. However, this may also make them more likely to learn idiosyncratic patterns which are highly specialised to each data modality, reducing knowledge transfer across modalities.4

Closing thoughts

I think the following is a question worth asking: Why should we expect Scientific AI to follow all the same trends (scaling laws, foundation models) as Consumer AI for language and vision?

Personally, I do believe that the idea of foundation models for molecular systems is really exciting, as this can potentially enable more accurate modelling of truly novel and data-scarce systems (which are usually what we care about in scientific discovery). I also think that scaling up data, parameters and computation has been the winning recipe for developing such unified and broadly applicable models.

So I’m very excited to see these pieces start to come together for molecular modelling. At the same time, new ideas in unified representation learning are needed to truly unlock knowledge transfer capabilities.

All this makes me really excited for OpenFold 3, where I hope we get to see such ablation studies done rigorously.

That being said, the top model on MatBench Discovery is still by a uni-modal eSEN (base architecture for UMA), not the omni-modal variant. I wonder why that’s the case, because the paper claims that UMA is the state-of-the-art for this benchmark, too.

There’s probably also something interesting to say about dataset curation. Clearly, the PDB is highly imbalanced due to historical reasons, so I’d be curious what happens if we tried smarter dataset curatuon strategies, similar to LLMs where this has had a huge impact.

Although, as seen in LLMs, this effect is regularised away if you have enough diverse data.

I like this post and think this is an important question to discuss. We recently highlighted some work on our blog (not our work!) using per-atom internal representations from NNPs for different downstream tasks—hopefully this does, as you say, provide us a way to bridge between the data-rich world of in silico data and the data-poor world of experimental measurements.

Blog: https://rowansci.com/blog/local-atomistic-environment